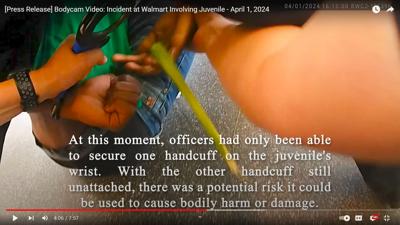

The body-camera video of a 13-year-old being forcibly arrested for selling palmetto roses outside a Summerville Walmart is not pleasant to watch. But it adds valuable context to an earlier video shot by a bystander that captured only the end of that encounter, after the young man had already been restrained and was uncooperative but no longer fighting.

Similarly, body-cam video released last week by North Charleston police makes it pretty clear that City Councilman Jerome Heyward was trying to throw his weight around when he told a police officer responding to a noise complaint at his bar “You know I don’t play no games” and “I’m gonna settle this once and for all,” then called the deputy police chief and handed his phone to the officer.

Regardless of the accuracy of the police report’s claim that Mr. Heyward was drunk — you don’t have to be falling down to be inebriated — it seems clear to us that the North Charleston police officer handled the complaint appropriately. In the Summerville case, the young man clearly was resisting police efforts to detain him, and he doesn’t appear to have been mistreated as badly as an attorney and social media comments suggest. Still, troubling questions remain as to why police were so determined to detain him.

Whatever we think of the police actions in either case, though, we are all better able to understand what happened — and to evaluate the behavior of police — now that we’ve seen the videos.

So in both cases, we applaud the decision to release them.

What we don’t applaud is a state law that leaves it entirely at the discretion of police and solicitors whether to release such police body-cam video, which is produced at taxpayer expense.

This is the opposite of how we treat most other evidence of police encounters with the public. When the video is shot from automobile dashcam, state law says it must be released to the public unless it would interfere with a police investigation, deprive someone of the right to a fair trial or qualify for another in a too-long but still limited list of exemptions. Ditto photographs, audio recordings and police incident reports.

We’ve too often seen police claim exemptions that clearly don’t qualify — just as we see with all sorts of government agencies. But in most cases, police comply with the law, and when they don’t, we can take them to court, and in almost all cases, the court orders them to release the information they’re trying to hide from the public. We don’t think anyone should have to file a lawsuit to see public information, but we do have that option.

When it comes to body-cam video, though, there’s no lawsuit to file, because police who hide the video from the public are not disobeying any law. Indeed, we’ve seen cases where police declare incorrectly that they’re not allowed to release the video.

Of course they are allowed to do so; they only have the option of refusing. While some police agencies routinely release body-cam video when it’s requested or when it involves an officer firing a weapon, too often police release the video only if they believe it shows them in a good light.

That gives us all legitimate reason to suspect that any video police don’t release shows them acting inappropriately or even illegally.

That’s unfortunate, because there may be cases where there actually are legitimate reasons not to release video that shows the police did nothing wrong. And there almost certainly are cases where attorneys have inaccurately told police they’re not allowed to release the video; after all, government attorneys have a track record of telling whatever governmental body they represent that they can’t release information when state law merely gives them the option of not releasing it.

Body-cam video was supposed to hold police accountable when they do something wrong and exonerate them when they don’t. There was never any justification for exempting it from the state’s Freedom of Information Act and letting police and prosecutors decide when we have a right to see the circumstances under which police harass, injure or even kill people in our names.

It’s an easy enough problem to fix. The Legislature should pass a law that treats body-cam video the same way it treats dashcam video, photographs and written reports: These videos should be presumed to be public information unless they qualify for one of the seven too-broad exemptions.

Click here for more opinion content from The Post and Courier.

North Charleston-provided body camera video showing the interaction between officer James Francis Ryan and City Councilman Jerome Heyward's on Feb. 24, 2024.