We don’t know why the master decided to sell the 9-year-old girl.

We don’t know whether Rose had days, hours or just minutes to prepare her little girl for her fate.

And we don’t know where young Ashley ended up.

What we know is that Rose, in an attempt to bestow a lifetime’s worth of maternal love upon her child, gave her Ashley a plain workaday sack to carry her few belongings and told her that in addition to the extra dress and the handfuls of pecans, that sack contained all of her love for the child to carry with her always.

Ashley’s story is lost to history, but the sack of her mother’s love that she carried away from her South Carolina home was passed down through the generations.

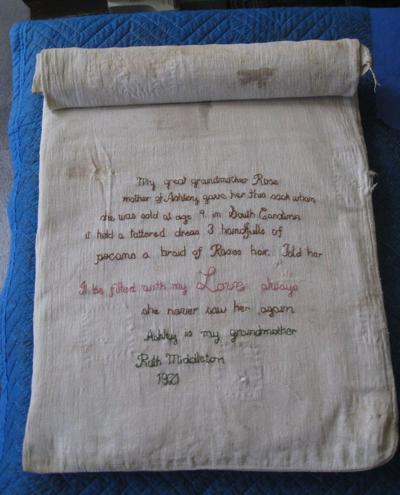

In 1921 Ruth Middleton, Ashley’s granddaughter, embroidered the story upon the sack. Then, in the early 2000s, it was discovered in Nashville, Tennessee.

Intrigued by the scant tale the sack told of its history, the discoverer attempted to find out more. That led her to Middleton Place, where officials were bowled over by the simple object.

Tracey Todd, vice president and chief operations officer at Middleton Place, said the sack, now known as Ashley’s Sack, strips away history to demonstrate the universal human truths of love and family.

“The reason it was saved was because it had so much power,” he said.

The discoverer, who has remained anonymous to the public, gave the sack to Middleton Place, which was able to determine that the materials dated to the 1850s.

It was probably a flour, seed or feed sack, an object toted by burly men that would normally have been thrown away, had it not carried a mother’s love.

“It probably stayed in the family … as a family heirloom,” Todd said.

Careful repairs to rips in the sack – again, care that wouldn’t normally have been taken with such a utilitarian item – indicate it was a precious object.

Todd said he thinks it unlikely that Rose and Ashley actually lived at Middleton Place. The Ashley River Road plantation was the Middletons’ family seat, but their wealth derived from working plantations, including three along the Combahee River in Colleton County, and it’s possible the mother and child lived there, he said.

Rose was not an unknown name among enslaved Africans, and there are Roses among the slaves listed in the Middleton records.

The sack has been displayed in the house museum at Middleton Place since it arrived. Its simple story never lost its power, Todd said: Whenever he gave a tour, he would have to ask visitors to read the tale themselves, as he couldn’t get through reading the words aloud.

“As human beings, we can relate to history, we can relate to a parent losing a child or being separated from a child,” he said.

Though the house and grounds at Middleton Place are filled with objects touched by enslaved people – the slaves would have polished the silver, dusted the furniture and washed the dishes so impressively displayed in the house today – there are very few items anywhere in the United States that actually belonged to an enslaved person.

Soon Ashley’s Sack will reach a much larger audience, as Todd hand-delivered the sack earlier this month to curators in Washington, D.C., who are gathering exhibits for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, scheduled to open on the National Mall in the fall of 2016.

Middleton Place is loaning the sack to the Smithsonian museum on a year-to-year basis.

Mary Elliot, museum specialist with the Smithsonian, is working on the Slavery and Freedom exhibit at the new museum under curator Nancy Bercaw.

The exhibit will show all aspects of the domestic slave trade, Elliot said – the economic, business side and the human side.

“This piece is very important to telling that human story,” she said.

The sack straddles the world of traditional oral storytelling and written – or in this case, embroidered – history.

Like Todd, Elliot said she felt the emotional pull of this artifact, along with many of the other pieces the museum has been gathering.

She said she had just finished reading a book that described the red flag flown in Charleston on slave auction days when she walked into a room at the South Carolina Historical Society prepped for the visiting historians from Washington and there it was – the red auction day flag.

She screamed in awe, she said. Not quite the detached, professional historian response, she said, but “you can’t help but be emotional when you see these things.”

The new museum will have three galleries to cover the totality of the African American experience – a history gallery; a community gallery, with exhibits on sports, the military and important institutions in African American life like churches, fraternities and sororities; and a culture gallery, with exhibits on the performing arts, visual arts and culture.

Both she and Todd said they believe that displaying the artifacts in Washington will encourage more people to come to South Carolina to see where this history occurred and, vice versa, that visitors to Charleston and Middleton Place will be encouraged to go to Washington to see these objects within the context of the larger American story.

And who knows – perhaps, with the larger audience the sack is bound to get in Washington, D.C. there will come along a visitor who can fill in the gaps of what we know about the lives of Rose and Ashley, two enslaved women who never saw each other again but whose love can still be felt today.