Anyone planning to pop the question this Valentine’s Day may want to consult Leonidas Harper’s 1858 missive to his future bride first. His Civil War-era marriage proposal sets a high bar.

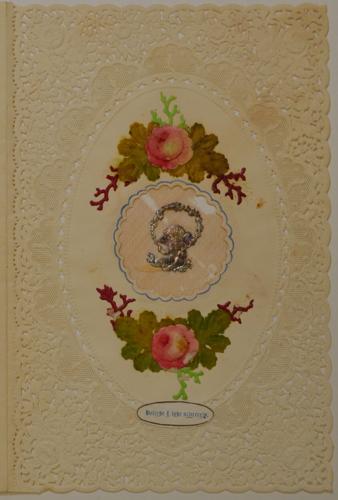

Preserved in a collection of letters by the Dorchester Heritage Center (DHC) in St. George, Leonidas Adolphus (“L.A.”) Harper’s offer for the hand of Elizabeth Catherine Dantzler is a beautifully penned example of why the DHC exists. It is also a gold standard for a well-articulated romance of the time and what laying a heart on the line of script can look like.

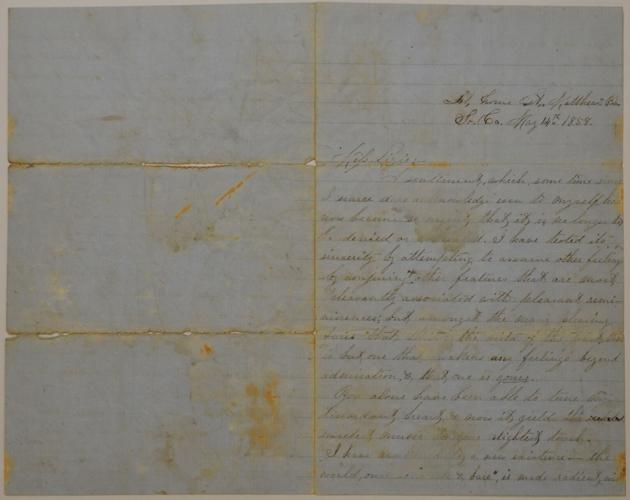

“Miss Lizzie –

… You alone have been able to tune my discordant heart, and now it yields the sweetest music to your slightest touch. I have awakened to a new existence — the world, once so “black and bare,” is made radiant with hope and verdant in the Spring of affection,” wrote Harper on May 14, 1858.

Born in 1833, the Elberton, Georgia native was hired by “Miss Lizzie’s” father to be a tutor for her and her numerous siblings. The second eldest daughter of Dr. Lewis and Mary Zimmerman Dantzler, “Miss Lizzie” was born in Orangeburg in 1841. The sweethearts began their correspondence before the Civil War and continued writing to each other throughout the bloody, four-year campaign.

Apparently, Harper’s romantic campaign and his skill with the pen succeeded, as the couple married before Harper joined the battle as a Confederate soldier. Surviving “The War Between the States,” the teacher and new husband finally returned to his bride, and the young couple settled in St. George and raised at least eight children there.

Harper’s proposal letter is among 100 or more epistles that the couple exchanged, and all are carefully archived by the DHC. The collection came to the organization through Charles George, one of the couple’s descendants.

“It is in your power to make me the happiest of men — or the reverse by dooming me to struggle, with a power that now has the mastery; but oh, if there is a cord within your heart which vibrates in unison with mine, touch that one alone and let the mingling of their notes be an emblem of the concordance of our future life …”

Evidence of this “future life” Harper spoke of, the couple’s progeny still live in the same family home that belonged to their ancestors, and according to DHC Director LaClaire Mizell and DHC Archivist Christine Rice, “there are Dantzlers all over upper Dorchester and lower Orangeburg Counties.”

“He’s very raw in his proposal. In today’s verbiage, he’s saying, ‘My life doesn’t make sense without you,’” said Mizell.

“In the other letters, they talk about what’s happening in their daily lives. She’s able to say, ‘This is what’s going on here,’ and he gives her advice on what to do, who to talk to … His letters tell her that even though he is at war, she is first and foremost in his mind.”

The Harper-Dantzler collection is among an estimated 500,000 documents, 10,000 artifacts and 4,500 books and magazines held safe by the DHC — the only repository in South Carolina that meets federal curation standards, accepts local collections and is open to researchers. Its treasures come from Lowcountry family’s attics and storage units before time, weather, animals or insects can destroy them.

Like history, marriages and other long-term partnerships also require preservation effort. Mizell noted that a radio show she had been listening to recently featured guests talking about why they had divorced. Most current statistics estimate that 50 percent of United States marriages end in divorce, and among younger generations, fewer people are getting married in the first place.

The Baby Boomers (1946-1965) were the first generation for whom divorce became acceptable, although it still came with taboos. Generation X (1965-1980), though, was the first wave of women for whom marriage wasn’t automatically “the done thing.” Now, only about 25 percent of Millenials and Generation Z’s (1981-1996 and 1997-2012, respectively) are tying the knot. That’s a decrease from Gen X’s 36 percent, the Boomers’ 48 percent and the Silent Generation’s (1928-1945) 65 percent.

For Harper and Dantzler’s Gilded Generation though, born 1822-1842, marriage was not only expected, but something you stuck with, through war, child-bearing, child-rearing, poverty, disaster, bringing home the wrong fabric for the parlor’s new curtains and pretty much everything else you could throw at two people.

“This couple was separated by years and miles and a war,” said Mizell. “You just don’t find the willingness to persevere through the challenges like you used to. A good marriage is going to take work.”

A heart-felt, soul-baring and carefully wrought proposal doesn’t hurt, either.

“Life cannot always be a dream,” wrote Harper.

“But if your affections are as firmly fixed as mine, we can contribute much to the happiness of each other, and together shun many of the snares which beset the path of life … Speak but the word and you have my pledge to do all that men dare do to make you happy; and surely if affection aided by untiring energy will accomplish it – I cannot fail.

If you prefer not giving an answer until you return home, I will not object — but a ‘yes’ by return mail would relieve me of much anxiety.”