Tax and planning policies have built-in biases in favor of suburban design, yet we cannot – on a national level or local level – sustain more suburbanization, Joe Minicozzi of Urban3 told a small group of elected officials, town staffers and Chamber members on Thursday.

Further, it is the urban core of cities and towns that does the hard lifting in terms of producing tax revenue and subsidizing outer areas, he said.

Minicozzi’s firm produced “The Value of Placemaking: The Cost and Impact of Development Patterns in the Tri-County Region” at the behest of a dozen local groups, including the Greater Summerville/Dorchester County Chamber of Commerce and the Berkeley-Charleston-Dorchester Council of Governments.

Thursday, he made presentations on the report in Charleston, North Charleston and Summerville.

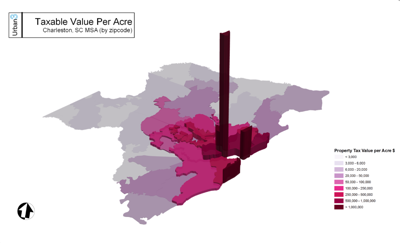

Minicozzi said local leaders should look at the value per acre of developments rather than overall value.

As an example, he pulled data from all the pre-1776 buildings in peninsular Charleston. Those buildings, which are built closely together, are generally more than one story and may have mixed uses of residential and commercial, altogether take up about 21 acres of space and paid $631,000 in county taxes in 2015.

By comparison, the Walmart at Tanger Outlets also takes up about 21 acres of space but paid $47,000 in county taxes in 2015.

Further, he said, the Walmart building is designed to depreciate quickly whereas the historic buildings have survived wars, fires, a major earthquake, floods and are still creating value for the city.

That value doesn’t have to be dependent on historic status but can be built, he said. He pointed to I’On and said that 9.7 acres of I’On Town Center produces the same value as the 66 acres of Northwoods Mall.

In the case of I’On, people moving in know they’re sacrificing some personal space because the homes are smaller and closer together. But the developer compensated by heavily investing in public space, Minicozzi said.

Building further from the urban core requires more roads, more water and sewer pipes and overall more cost to local government: in effect, he said, local government is subsidizing people's choice to live farther from the center of town.

Even if a developer undertakes the initial cost to build roads, the developer then deeds those roads to the town or county, thus handing the local government a liability that will come back to haunt it in 40 years when the road needs repair, he said.

In Summerville, downtown has an average value per acre of $2.7 million compared to the overall city average of $376,000, he said.

Minicozzi, whose firm is based in Asheville, said there was pushback when a group started advocating for redevelopment of Asheville's downtown, which in the 1980s and 1990s wasn't the hip artsy area it is now but a rundown relic filled with empty buildings. Opponents said that Asheville was a rural mountain town, not an urban area.

But, he said, the intent wasn’t to force everyone to live downtown.

“It was to provide that opportunity to the 30 percent of the market that wanted it,” he said.

He advocated changing policies to require that buildings downtown have more than one story and to eliminate a requirement for parking spaces. In Asheville, the parking space requirement was lifted and residents of apartment buildings purchased parking passes to city garages.

After the meeting, town Director of Planning Jessi Shuler said those are ideas the town is looking at as it revamps its planning code.

Mixed residential/commercial use within the same buildings is currently allowed, she said, but the wording in the code is so confusing that it’s not practicable.

Before the meeting, as the group waited for Minicozzi to arrive from Charleston, local architect Dennis Ashley said the common complaint here is that building more in the downtown Summerville and Main Street area will simply increase traffic. But, he said, if people live in that area then they won’t need to drive through it to get home – they will be home.

Downtown Summerville shouldn’t be thought of simply as a transit point for people from outer subdivisions, he said.

After the meeting, Minicozzi told the Journal Scene that just because previous property owners have been able to build low-density subdivisions doesn’t mean the town and county have to continue to allow property owners to build such developments.

We “have to shift the discussion,” he said.

Way back in 1974, the Nixon administration funded research that became the three-volume “The Costs of Sprawl.”

Yet even after that study, even after the gas crisis of 1973, Minicozzi said, we haven’t been able to learn from past mistakes.